Swifts in the tower

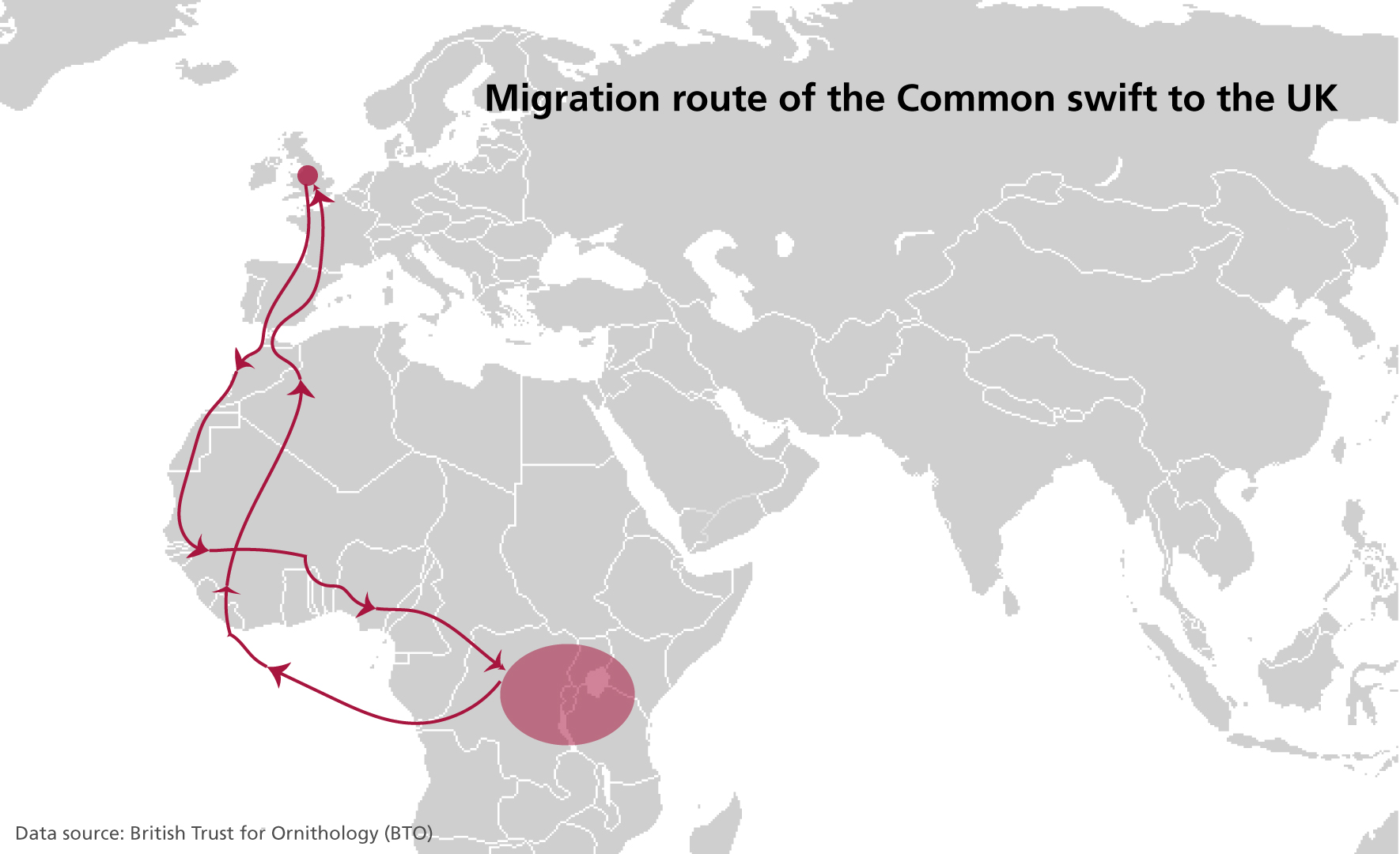

Each spring, swifts return to the UK after their long migration from Africa. For years, the Museum tower has been a favourite nesting site, and our live camera reveals the nesting birds inside from May-August.

The Museum tower is a nesting site for European swifts and they are a familiar summer sight here. Once fledged, Common or European Swifts (Apus apus) spend practically their entire life in flight. They feed, sleep, and collect nesting material on the wing. The only time a swift stops flying is when it is breeding, although they sometimes even mate without stopping.

The swifts’ nest boxes are well hidden and accessing them involves a cramped climb to the very top of the tower. But our webcam reveals this hidden space, showing chicks growing each summer. Cameras have been installed in two of the nest boxes, and the images are streamed online from May to early September.

The colony of swifts here has been the subject of a research study since May 1947, when Elizabeth Lack and David Lack installed nest boxes in the tower. It is one of the longest continuous studies of a single bird species in the world, and has contributed much to our knowledge of the swift. In 1956, Swifts in a Tower was published, detailing the Lacks’ work on the colony. In 2018, the book was re-published, offering a fascinating insight into the swifts which continue to nest in the tower.

Sadly, the swift population in the UK has fallen by 42 percent since 1994. This may be due to a lack of nesting sites and food. The Oxford Swift City project launched by the RSPB in 2017 aims to improve the conservation of swifts in Oxford by raising local awareness.

In honour of our 2014 Wildlife Photographer of the Year Exhibition, the Museum held a swift photograph competition. Mastery of the Skies by Judith Wakelam was chosen as the winner. Below you can see some of the other competition entries.

Common Swifts (Apus apus) have coal-black or brown plumage, although they appear black against the sky, with a pale throat. Their long, thin, rigid and scythe-shaped wings are built for efficient gliding flight over long distances. They are very fast fliers and are recognised by their high-pitched screaming call.

Swift beaks have a wide gape to catch a variety of insects and airborne spiders while on the wing, and they are able to fly hundreds of kilometres a day while feeding, and even while sleeping. A pair of swifts feeding young may catch some 20,000 insects and spiders in a single day.

Their short legs and strong feet, with all four toes facing forwards, are used to hang on to vertical surfaces, to crawl into their nests or for fighting intruders. Contrary to common belief, swifts can take off from the ground, although they are unable to walk or perch on the ground.

Swifts have an exceptionally long life span for their size. Once they reach adulthood they usually live for about 6 years. They are extremely faithful to their nesting site, returning to the Museum tower year after year. They start to arrive in the last days of April and the fledglings usually leave around the beginning of August, setting off, almost immediately, for Africa, followed by their parents a week or so later.

The males usually arrive first and take possession of the nest box. Mating takes place and two or three eggs are laid, normally in the last week of May, about a fortnight after the female’s arrival. Both parents brood the eggs, and the incubation takes about 19 days. The eggs hatch around the middle of June and both parents feed the naked nestlings. They bring them small balls of food, packed into their throat, which consist of hundreds of tiny insects and spiders held together by saliva. The nesting period of swifts at Oxford varies from five to eight weeks. The young swifts leave the nest independently of their parents when their wings have reached full or nearly full length.

© Judith Wakelam

© Judith Wakelam

The swifts’ nest is a simple shallow bowl which is used year after year. Each season it is renewed with fresh material. Swifts use anything available to them: feathers, leaves, grass, seeds, flower petals and even scraps of paper or tinfoil! Both male and female take part in building the nest

The Oxford Swift Research Project The colony of swifts which nest in the Museum has been the subject of a research study since May 1948. It is one of the longest continuous studies of a single bird species in the world, and has contributed much to our knowledge of the swift.

Swifts had been nesting inside the ventilator shafts of the Museum tower for many years when David Lack, the head of the Edward Grey Institute at the Department of Zoology, began the swift research project. Swifts use nesting sites which are inaccessible to predators to safeguard the eggs and chicks. The parents are also quite vulnerable when nesting. Swifts had proved a difficult species to study as they spend most of their lives in the air, but Lack realised that the swift colony in the Museum would be ideal for long term research. This is one of the longest running studies of any species of bird, and has contributed greatly to our knowledge. In 1956, the book Swifts in a Tower was first published and details David and Elizabeth Lack’s work on the colony of swifts in the Museum. It describes the setting up of the project and reviews other swift species. This year David Lack's book has been re-published. It offers a fascinating insight into the swifts nesting in the tower of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. Different editions of Lack's book are also available in the Museum library.